Thought Catalog > Learning from Impressionism 3

European Painting 1850-1900 – Chapter 3

NEW COMPOSITION

As new subject matter immerged from the second half of 19th-century, painting composition also began to change. To a young group of experimental painters, conventional composition techniques, such as, symmetry, balance, triangulation, placement of horizon line, background and foreground, perspective, carried connotations from the ages past; and therefore, were subject to re-examination. In some cases, such conventions were completely abandoned. In searching for the new spirit of the age, not only were painters looking for fresh approaches that could distance themselves from the connotation of classical traditions, but also an expression that was truly authentic to the rapidly changing modernity.

Degas’ Modern Enigma

In many ways, Edgar Degas was at the forefront of such compositional re-thinking during this period. Like Courbet and Manet before him, Degas also subscribed a form of realism based on direct observation of contemporary life.

Unlike Courbet or Manet, however, Degas was far less convinced that authentic expression of contemporary life could be based on adaptation from historical subject matter and former compositional convention. This was evident by the fact that though he started off with historical painting, he soon abandoned it and turned his attention towards contemporary portraiture. In fact, Degas made frequent observations of the people in his social circles and in particular, the daily life his own family. At the same time, the composition of his portraiture was gradually shifting away from a rather rigid and idealized formalism towards a more relaxed and down to earth realism, showing how people really looked like in their daily life.

Fig.14 Edgar Degas, A Woman Seated Besides a Vase of Flowers, 1865

By 1865, Degas’s search for modernity began to crystallize when he painted A Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers (Fig.14). The painting was built on juxtaposing between the flowers in the middle and a woman on the right. What seemed immediately unusual was how the woman was placed off-centered. She leaned on her right arm with her left arm cropped and her eyesight focused beyond the picture frame. The composition was decidedly un-classical. The compositional imbalance and figural incompleteness would have been unthinkable under the precepts of the neo-classical masters. But to Degas, the balanced imageries from the neo-classical era could not be adapted to adequately reflect the complex human psychology that interested him. He needed a compositional approach to express how he felt at the moment of his transitory observation. He seemed convinced to express his sentiment by juxtaposing two seemingly unconnected objects, and in this case, the vase of flowers and the woman. It prompted the viewers to ponder on their exact relationship; and in particular, the nature of the woman’s contemplative gaze. Perhaps she was daydreaming or lost in her own thoughts. The painting offered no direct answer though perhaps clues for speculations. Yet, the eccentricity created from this somewhat disjointed composition brought out the enigma of the woman’s gaze, which never failed to intrigue its viewers even until today.

For the first time since Degas had abandoned historical paintings, off-centered asymmetry, intentional disjointedness and the partially cropped figures would increasingly become Degas’s unique approach to composition. Despite this promising though unusual approach, this painting remained statically close to his former work. For it had not yet possessed the vitality and the sense of movement so commonly associated with his later work. Over the next several years, Degas continued to paint his observation on horses, ballet dancers and the people he met. Though he was still uncertain of his style, his paintings gradually displayed a greater degree of conviction and liveliness.

Spontaneous Modernism

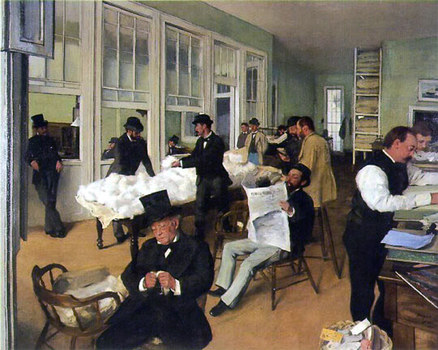

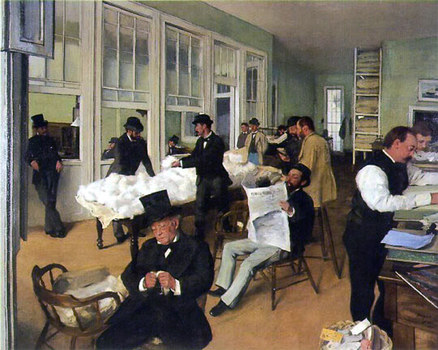

After finishing his enlistment under the Franco-Prussian War in 1872, Degas left Paris for an extended stay in New Orleans. As this former French colony was quickly becoming a major seaport of the new world, Degas must have found the post civil war atmosphere in New Orleans intriguing. During his stay, he visited his uncle’s office and painted the Cotton Office in New Orleans (Fig.15). The painting showed more than a dozen of people going about their daily business including checking the cotton quality; reviewing business paperwork; discussing business deal; reading newspaper; cleaning one’s own spectacles and someone simply leaning by the window watching idly. The relative laid-back work style and the apparent absence of formality in the office caught Degas’s attention and led him to capture the spirit of the atmosphere in a painting.

Fig.15 Edgar Degas, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, 1873

Given his preference to work in the studio, it was unlikely that Degas set up his canvas inside the Cotton Exchange office to finish this painting. He would have to make preparatory sketches rather quickly as he quietly observed each individual and followed what was unfolding in front of him. His intention was to capture their most natural postures and deliberately avoided them posing in front of the canvas. The sketching process surely took time. And more than likely, each sketched figure went through further study and refinement back in the studio until the most natural posture was achieved. But his prolific visual memory must have helped him later on to recreate a composition that was most representative to what he saw. Still, it was a huge undertaking to compose fourteen figures. The final painting revealed a composition contained within an interior space with exceptional detail. Much like the backdrop of a stage, the simple though functional room partitions were set up as background. The unadorned interior was delineated with a vantage point to draw us deep into the room. All the standing figures were then carefully placed at eye level with none one of them blocking the face of another person. The relatively large sitting figure at the foreground were balanced by numerous smaller figures standing in the back; while two men busily reviewing paper work on the right were contrasted and balanced by the man watching idly on the left. This delicate arrangement of the figures achieved an overall compositional balance. Yet, their relative sizes due to perspective foreshortening prompted our eyes to glance back and forth among them, creating an animated mental image with latent movement. As we examined each person more closely, their respective postures served as a narrative to what they did and therefore gave us an immediate understanding to what it must have been like in the mist of their daily business.

Taken as a whole, the laid-back business atmosphere of the office came alive. In fact, the masterful composition created an impression as if the painting was drawn up spontaneously without any premeditation. The immediacy generated was not unlike a photographic snapshot capable of giving the viewers the feeling of personal presence in the room. By his late thirties, years of continual experiment had led Degas to capture decisive artistic moments in which he found expression through highly animated compositions with unmistakable spontaneity and immediacy.

When he return to Paris in 1873, this painting on Cotton Office in New Orleans was very well received and it was eventually purchased by Musee Municipal de Pau. Invigorated by its success, Degas now firmly believed that modern painting should reflect contemporary life. He persuaded his Parisian colleagues to follow suit. Later in the same year, he went on to help organize what would be called the first impressionist exhibition. Since then, many regarded Degas as the most important figure among his generation of emerging impressionist painters.

New Vantage Point and Compositional Freedom

In 1875, Degas painted Place de la Concorde (Fig.16). In his typical instinctive manner, Degas recorded his transitory observation of his aristocratic artist friend Vicomte Lepic and his two daughters taking a walk with their dog in the largest public square in Paris. Once again, the off-centered asymmetry; unrelated figures with disconnected eyesight; and partially cropped figure were all carried out with his signatory spontaneous snapshot approach. Even his brushstrokes now seemed broader; and his figures looked flatter than those he painted before. It was perhaps a reflectance of his involvement and the influence he received from his Parisian art circle. Regardless, the atmosphere of the painting communicated an eerie sense of isolation and loneliness.

Fig.16 Edgar Degas, Place de la Concorde, 1875

Fig.17 Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street Rainy Day, 1877

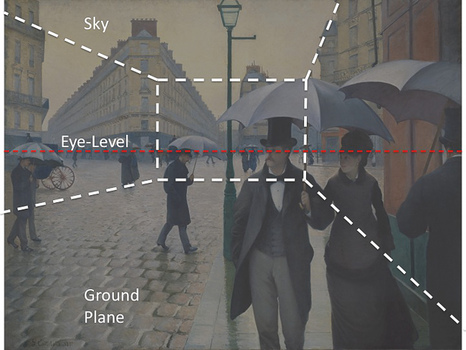

Fig.18 Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street Rainy Day, compositional analysis

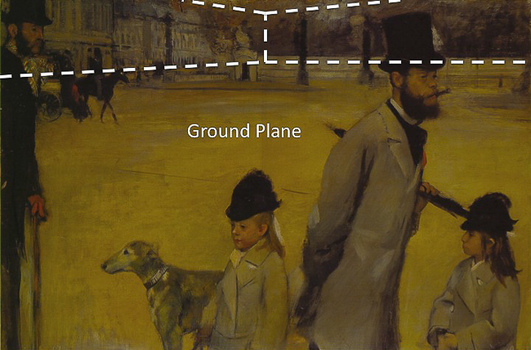

Fig.19 Edgar Degas, Place de la Concorde, compositional analysis

One way to understand the composition of Place de la Concorde was to compare it to his contemporary Paris Street Rainy Day by Gustave Caillebotte in 1876 (Fig.17). Both paintings provided up-close portraiture of outdoor Parisians. Both were composed as a snapshot of the scene with a person partially cropped at the edge of the picture. But we notice the vantage points chosen by the painters and their respective spatial delineation was totally different. Caillebotte achieved spatial clarity and accuracy by looking at the scene horizontally at normal eye level with his picture plane remained vertical. The urban space was clearly defined by its surrounding architecture, street surface and the sky (Fig.18). Obviously, Caillebotte followed traditional approach in which space was typically drawn up undistorted and with properly defined boundaries. Such clarity of urban space did not exist in Place de la Concorde. What we found, however, was a large empty ground plane in the middle of the picture while the sky was cut off from view (Fig.19). Quite unlike Caillebotte, Degas did not choose his normal eye level as his vantage point. Instead, he seemed to stand above his normal eye level and looking slightly downward, showing more than usual amount of ground plane. While we may never know the exact reason behind this unconventional vantage point, Degas’ determination to outdo and surprise his contemporaries probably played a role in it.

Fig.20 Edgar Degas, Cotton Office, 1873

As we examine the progress of Degas’s paintings closely, this unconventional vantage point seemed much more intentional than accidental. In order to realize compositional freedom unencumbered by traditional spatial delineation, Degas experimented with new vantage points beyond traditional perspective. As successful as his New Orleans Cotton Exchange (Fig.15), the spatial treatment of the interior was still rather conventional. The strict adherence to the laws of interior perspective resulted in a painting with its content essentially contained within a rigid six-sided “box.” While this traditional perspective illustrated the room with clarity, it did restrict Degas from trying out other compositional invention. In fact, soon after the New Orleans Cotton Exchange, Degas painted another interior of the Cotton Exchange office with only 3 figures in a rather flattened interior (Fig.20). In comparison to the first, the second painting seemed loosely constructed for it lacked the meticulous craftsmanship of a traditional interior perspective. In his letter to his friend, however, Degas actually considered the second painting of the cotton office a further development of his artistic endeavor. Even before New Orleans Cotton Exchange, Degas had been painting horses and ballet dancers and experimenting continuously with various vantage points to capture his fascination on those subjects. But it became clear by mid 1870s that nothing seemed to be as satisfying to Degas as these instinctive vantage points in reflecting his split second glimpses of these fleeting yet intensely beautiful moments.

Fig.21 Edgar Degas, The Dance Class, 1880

Fig.22 Edgar Degas, The Dance Lesson, 1879

By mid 1870s and 1880s, Degas produced his highly acclaimed series of dance class paintings. It included The Dance Class in 1880 (Fig. 21). Compositional techniques initiated in Place de La Concorde were continued into the dance halls and rehearsal rooms with remarkable similarity. Spaces were reduced into its simplicity with walls and ceiling partially cut off or omitted altogether. Large and empty ground plane stretched across the entire picture. Rudimentary spaces were intentionally painted as monotonous in order to set the stage on which Degas could fully unleash his pictorial drama. Degas then turned his concentration to his female ballerinas and their nimble bodily movements. With his tremendous sensitivity to female body and masterful craftsmanship, he vividly recorded the gesture of each dancer with exactitude and superlative liveliness. He organized them in the picture diagonally or sometimes in groups, but always uncluttered and mindful of their figural clarity and graceful silhouette. Colorful, elegant, graceful, and brimming with energy, Degas gave us rare glimpses of these magnificent young female ballerinas dancing across the picture just as they would roam freely during dancing practices. These pictures (Fig. 22, 23) possessed all the qualities Degas had sought for throughout his career and vividly reflected his fascination with the dancing girls, which lasted for the rest of his life. With these paintings, Degas reached new height in both pictorial dynamism and compositional invention.

Fig.23 Edgar Degas, In the Dance Studio

From Classicism to Modernity

We shall recognize that despite his innovative and sometimes unusual pictorial compositions, one would be mistaken to consider Degas simply as a radical modernist painter. Quite the contrary, Degas never wavered in his pursuit of classical beauty since the days he received his training. The impact from Ingres on his appreciation of human figure never departed him. It would be far more appropriate to consider Degas as the key figure bridging between the classical traditional and the emerging modern expression. For his painting exhibited unmistakable clarity and beauty of the human form on one hand while blended with his audacity on compositional innovation on the other. While his influence to his contemporary painters was undeniable, the spontaneity and immediacy of his composition also made his way of seeing the world an inspiration to many photographers of the 20th century. In many ways, his legacy went beyond the period of impressionism and lives on even until today.

NEW COMPOSITION

As new subject matter immerged from the second half of 19th-century, painting composition also began to change. To a young group of experimental painters, conventional composition techniques, such as, symmetry, balance, triangulation, placement of horizon line, background and foreground, perspective, carried connotations from the ages past; and therefore, were subject to re-examination. In some cases, such conventions were completely abandoned. In searching for the new spirit of the age, not only were painters looking for fresh approaches that could distance themselves from the connotation of classical traditions, but also an expression that was truly authentic to the rapidly changing modernity.

Degas’ Modern Enigma

In many ways, Edgar Degas was at the forefront of such compositional re-thinking during this period. Like Courbet and Manet before him, Degas also subscribed a form of realism based on direct observation of contemporary life.

Unlike Courbet or Manet, however, Degas was far less convinced that authentic expression of contemporary life could be based on adaptation from historical subject matter and former compositional convention. This was evident by the fact that though he started off with historical painting, he soon abandoned it and turned his attention towards contemporary portraiture. In fact, Degas made frequent observations of the people in his social circles and in particular, the daily life his own family. At the same time, the composition of his portraiture was gradually shifting away from a rather rigid and idealized formalism towards a more relaxed and down to earth realism, showing how people really looked like in their daily life.

Fig.14 Edgar Degas, A Woman Seated Besides a Vase of Flowers, 1865

By 1865, Degas’s search for modernity began to crystallize when he painted A Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers (Fig.14). The painting was built on juxtaposing between the flowers in the middle and a woman on the right. What seemed immediately unusual was how the woman was placed off-centered. She leaned on her right arm with her left arm cropped and her eyesight focused beyond the picture frame. The composition was decidedly un-classical. The compositional imbalance and figural incompleteness would have been unthinkable under the precepts of the neo-classical masters. But to Degas, the balanced imageries from the neo-classical era could not be adapted to adequately reflect the complex human psychology that interested him. He needed a compositional approach to express how he felt at the moment of his transitory observation. He seemed convinced to express his sentiment by juxtaposing two seemingly unconnected objects, and in this case, the vase of flowers and the woman. It prompted the viewers to ponder on their exact relationship; and in particular, the nature of the woman’s contemplative gaze. Perhaps she was daydreaming or lost in her own thoughts. The painting offered no direct answer though perhaps clues for speculations. Yet, the eccentricity created from this somewhat disjointed composition brought out the enigma of the woman’s gaze, which never failed to intrigue its viewers even until today.

For the first time since Degas had abandoned historical paintings, off-centered asymmetry, intentional disjointedness and the partially cropped figures would increasingly become Degas’s unique approach to composition. Despite this promising though unusual approach, this painting remained statically close to his former work. For it had not yet possessed the vitality and the sense of movement so commonly associated with his later work. Over the next several years, Degas continued to paint his observation on horses, ballet dancers and the people he met. Though he was still uncertain of his style, his paintings gradually displayed a greater degree of conviction and liveliness.

Spontaneous Modernism

After finishing his enlistment under the Franco-Prussian War in 1872, Degas left Paris for an extended stay in New Orleans. As this former French colony was quickly becoming a major seaport of the new world, Degas must have found the post civil war atmosphere in New Orleans intriguing. During his stay, he visited his uncle’s office and painted the Cotton Office in New Orleans (Fig.15). The painting showed more than a dozen of people going about their daily business including checking the cotton quality; reviewing business paperwork; discussing business deal; reading newspaper; cleaning one’s own spectacles and someone simply leaning by the window watching idly. The relative laid-back work style and the apparent absence of formality in the office caught Degas’s attention and led him to capture the spirit of the atmosphere in a painting.

Fig.15 Edgar Degas, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, 1873

Given his preference to work in the studio, it was unlikely that Degas set up his canvas inside the Cotton Exchange office to finish this painting. He would have to make preparatory sketches rather quickly as he quietly observed each individual and followed what was unfolding in front of him. His intention was to capture their most natural postures and deliberately avoided them posing in front of the canvas. The sketching process surely took time. And more than likely, each sketched figure went through further study and refinement back in the studio until the most natural posture was achieved. But his prolific visual memory must have helped him later on to recreate a composition that was most representative to what he saw. Still, it was a huge undertaking to compose fourteen figures. The final painting revealed a composition contained within an interior space with exceptional detail. Much like the backdrop of a stage, the simple though functional room partitions were set up as background. The unadorned interior was delineated with a vantage point to draw us deep into the room. All the standing figures were then carefully placed at eye level with none one of them blocking the face of another person. The relatively large sitting figure at the foreground were balanced by numerous smaller figures standing in the back; while two men busily reviewing paper work on the right were contrasted and balanced by the man watching idly on the left. This delicate arrangement of the figures achieved an overall compositional balance. Yet, their relative sizes due to perspective foreshortening prompted our eyes to glance back and forth among them, creating an animated mental image with latent movement. As we examined each person more closely, their respective postures served as a narrative to what they did and therefore gave us an immediate understanding to what it must have been like in the mist of their daily business.

Taken as a whole, the laid-back business atmosphere of the office came alive. In fact, the masterful composition created an impression as if the painting was drawn up spontaneously without any premeditation. The immediacy generated was not unlike a photographic snapshot capable of giving the viewers the feeling of personal presence in the room. By his late thirties, years of continual experiment had led Degas to capture decisive artistic moments in which he found expression through highly animated compositions with unmistakable spontaneity and immediacy.

When he return to Paris in 1873, this painting on Cotton Office in New Orleans was very well received and it was eventually purchased by Musee Municipal de Pau. Invigorated by its success, Degas now firmly believed that modern painting should reflect contemporary life. He persuaded his Parisian colleagues to follow suit. Later in the same year, he went on to help organize what would be called the first impressionist exhibition. Since then, many regarded Degas as the most important figure among his generation of emerging impressionist painters.

New Vantage Point and Compositional Freedom

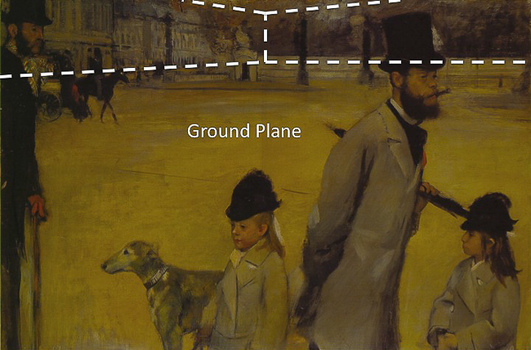

In 1875, Degas painted Place de la Concorde (Fig.16). In his typical instinctive manner, Degas recorded his transitory observation of his aristocratic artist friend Vicomte Lepic and his two daughters taking a walk with their dog in the largest public square in Paris. Once again, the off-centered asymmetry; unrelated figures with disconnected eyesight; and partially cropped figure were all carried out with his signatory spontaneous snapshot approach. Even his brushstrokes now seemed broader; and his figures looked flatter than those he painted before. It was perhaps a reflectance of his involvement and the influence he received from his Parisian art circle. Regardless, the atmosphere of the painting communicated an eerie sense of isolation and loneliness.

Fig.16 Edgar Degas, Place de la Concorde, 1875

Fig.17 Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street Rainy Day, 1877

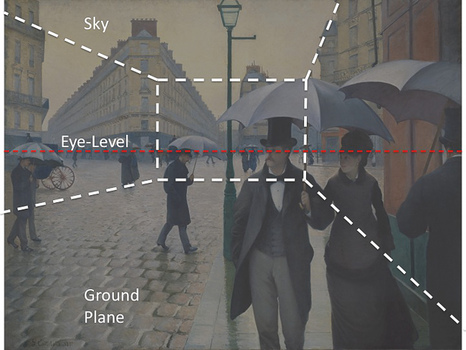

Fig.18 Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street Rainy Day, compositional analysis

Fig.19 Edgar Degas, Place de la Concorde, compositional analysis

One way to understand the composition of Place de la Concorde was to compare it to his contemporary Paris Street Rainy Day by Gustave Caillebotte in 1876 (Fig.17). Both paintings provided up-close portraiture of outdoor Parisians. Both were composed as a snapshot of the scene with a person partially cropped at the edge of the picture. But we notice the vantage points chosen by the painters and their respective spatial delineation was totally different. Caillebotte achieved spatial clarity and accuracy by looking at the scene horizontally at normal eye level with his picture plane remained vertical. The urban space was clearly defined by its surrounding architecture, street surface and the sky (Fig.18). Obviously, Caillebotte followed traditional approach in which space was typically drawn up undistorted and with properly defined boundaries. Such clarity of urban space did not exist in Place de la Concorde. What we found, however, was a large empty ground plane in the middle of the picture while the sky was cut off from view (Fig.19). Quite unlike Caillebotte, Degas did not choose his normal eye level as his vantage point. Instead, he seemed to stand above his normal eye level and looking slightly downward, showing more than usual amount of ground plane. While we may never know the exact reason behind this unconventional vantage point, Degas’ determination to outdo and surprise his contemporaries probably played a role in it.

Fig.20 Edgar Degas, Cotton Office, 1873

As we examine the progress of Degas’s paintings closely, this unconventional vantage point seemed much more intentional than accidental. In order to realize compositional freedom unencumbered by traditional spatial delineation, Degas experimented with new vantage points beyond traditional perspective. As successful as his New Orleans Cotton Exchange (Fig.15), the spatial treatment of the interior was still rather conventional. The strict adherence to the laws of interior perspective resulted in a painting with its content essentially contained within a rigid six-sided “box.” While this traditional perspective illustrated the room with clarity, it did restrict Degas from trying out other compositional invention. In fact, soon after the New Orleans Cotton Exchange, Degas painted another interior of the Cotton Exchange office with only 3 figures in a rather flattened interior (Fig.20). In comparison to the first, the second painting seemed loosely constructed for it lacked the meticulous craftsmanship of a traditional interior perspective. In his letter to his friend, however, Degas actually considered the second painting of the cotton office a further development of his artistic endeavor. Even before New Orleans Cotton Exchange, Degas had been painting horses and ballet dancers and experimenting continuously with various vantage points to capture his fascination on those subjects. But it became clear by mid 1870s that nothing seemed to be as satisfying to Degas as these instinctive vantage points in reflecting his split second glimpses of these fleeting yet intensely beautiful moments.

Fig.21 Edgar Degas, The Dance Class, 1880

Fig.22 Edgar Degas, The Dance Lesson, 1879

By mid 1870s and 1880s, Degas produced his highly acclaimed series of dance class paintings. It included The Dance Class in 1880 (Fig. 21). Compositional techniques initiated in Place de La Concorde were continued into the dance halls and rehearsal rooms with remarkable similarity. Spaces were reduced into its simplicity with walls and ceiling partially cut off or omitted altogether. Large and empty ground plane stretched across the entire picture. Rudimentary spaces were intentionally painted as monotonous in order to set the stage on which Degas could fully unleash his pictorial drama. Degas then turned his concentration to his female ballerinas and their nimble bodily movements. With his tremendous sensitivity to female body and masterful craftsmanship, he vividly recorded the gesture of each dancer with exactitude and superlative liveliness. He organized them in the picture diagonally or sometimes in groups, but always uncluttered and mindful of their figural clarity and graceful silhouette. Colorful, elegant, graceful, and brimming with energy, Degas gave us rare glimpses of these magnificent young female ballerinas dancing across the picture just as they would roam freely during dancing practices. These pictures (Fig. 22, 23) possessed all the qualities Degas had sought for throughout his career and vividly reflected his fascination with the dancing girls, which lasted for the rest of his life. With these paintings, Degas reached new height in both pictorial dynamism and compositional invention.

Fig.23 Edgar Degas, In the Dance Studio

From Classicism to Modernity

We shall recognize that despite his innovative and sometimes unusual pictorial compositions, one would be mistaken to consider Degas simply as a radical modernist painter. Quite the contrary, Degas never wavered in his pursuit of classical beauty since the days he received his training. The impact from Ingres on his appreciation of human figure never departed him. It would be far more appropriate to consider Degas as the key figure bridging between the classical traditional and the emerging modern expression. For his painting exhibited unmistakable clarity and beauty of the human form on one hand while blended with his audacity on compositional innovation on the other. While his influence to his contemporary painters was undeniable, the spontaneity and immediacy of his composition also made his way of seeing the world an inspiration to many photographers of the 20th century. In many ways, his legacy went beyond the period of impressionism and lives on even until today.